Are Poker Players Secretly Risk Averse?

Three videos show when gamblers turn down risky bets

When you think of poker players, "risk taker" probably tops the list. After all, they’re literally betting thousands of dollars on uncertain outcomes. But dig a little deeper and you’ll find a fascinating twist: even professional poker players often behave in ways economists would describe as risk averse.

In this post, drawn from our recent YouTube video, I explore how poker hands reveal core principles from behavioral economics—especially risk aversion, expected value, and marginal utility.

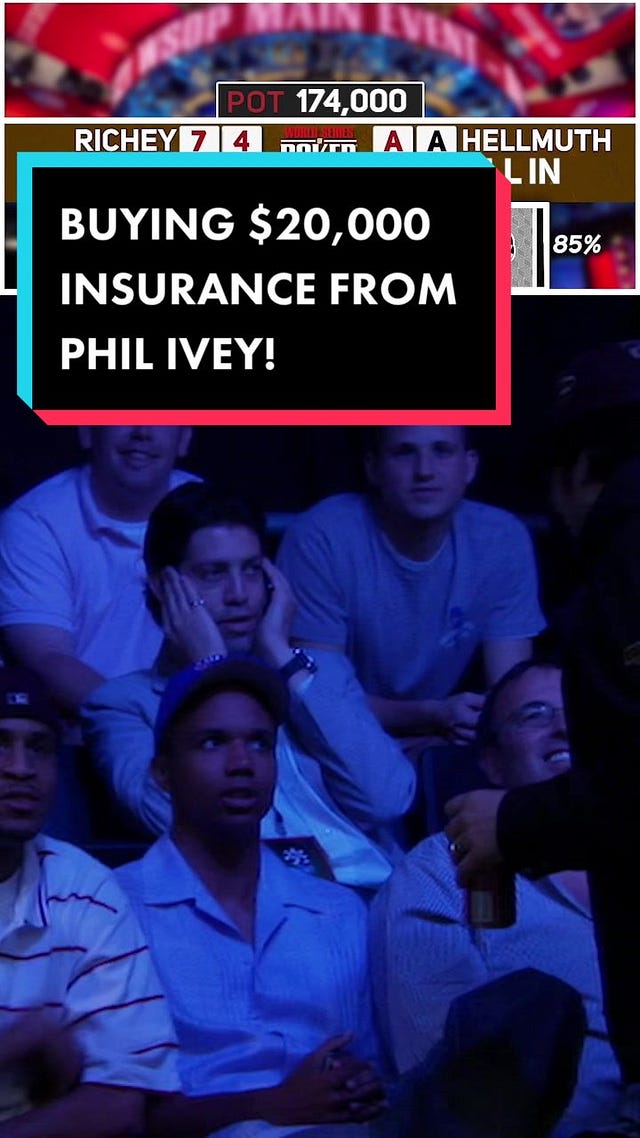

Hand #1: Phil Hellmuth Buys Insurance While Holding Aces

In a televised high-stakes hand, Phil Hellmuth holds pocket aces and is heavily favored to win. Still, he chooses to buy insurance from fellow pro Phil Ivey—paying $20,000 to guarantee a $90,000 payout only if he loses the hand. The fair value of the insurance (based on odds) was closer to $15,000.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Takeaway: Hellmuth willingly pays a $5,000 premium to eliminate risk, showing textbook risk aversion. Even poker legends dislike uncertainty when the stakes are high enough.

Hand #2: Brad Owen “Runs It Twice” to Smooth Variance

In another scenario, Brad Owen faces an all-in with pocket queens against ace-king. Rather than run the hand once, the players agree to run it twice—two separate board runouts, splitting the pot between them.

Nothing changes in terms of expected value. But variance is reduced. Imagine that the hand would have been exactly 50/50 to win or lose. By running it twice, the odds are now:

25% win both runouts (scoop the pot)

50% win one, lose one (break even)

25% lose both

Takeaway: Running it twice is a variance-smoothing technique. It reduces the emotional and financial whiplash that can sink even skilled players—especially pros who rely on long-run gains.

Hand #3: A Teacher Folds Pocket Aces for a Guaranteed $50,000

The most extreme case of risk aversion came in a PokerStars special where an amateur teacher, staked with $100,000, folded pocket aces pre-flop. Why? He had just won a big pot and was sitting on a $50,000 profit—money he could keep if he didn’t lose it.

Despite holding the strongest starting hand in poker, he chose the sure thing.

From an economics standpoint, this is risk aversion on full display. The teacher effectively “paid” over $100,000 in expected value to lock in a life-changing payday. When you factor in diminishing marginal utility—the idea that each additional dollar is worth less to you than the last—the decision makes more sense.

(That said, if you’re ever at a poker table and think you might fold pocket aces, it’s time to leave the game!!!)

So, What’s the Lesson?

Even professional gamblers don’t treat money the same way all the time. We’re all subject to emotional responses, loss aversion, and the desire for certainty. These hands remind us that:

Risk aversion is real—even among gamblers

Insurance markets exist in everyday and unusual settings (like poker)

Variance matters just as much as expected value

Marginal utility shapes how we value additional income

Poker offers a rich playground for observing economic behavior in real time—and not just in theory

Watch the full discussion here:

Subscribe to the for more lessons like this.

Let me know what you think. Have you ever made a “rational” decision that looked irrational on paper? Or hedged against your own team just to protect your emotions? I’d love to hear your take.